DERUCHETTE'S GARDEN

'More a flower than a woman'

Déruchette is the young niece of Mess Lethierry, a canny Guernsey ship-builder. She is the apple of his eye and lives with him in St Sampson’s parish in a new house he has built, Les Bravées. She spends her time playing the piano, tending her garden, and going to church. The garden of Les Bravées is surrounded by a low wall. Gilliatt, her admirer, hides nearby and observes her in the garden, and plays to her on his Anglo-Norman bagpipes – or, as Victor Hugo famously insisted, his ‘bugpipe’ – always the same tune, a tune she often plays at the piano: the story of a Romantic rebel and fugitive, ‘Bonny Dundee’.

‘Déruchette had at times an air of bewitching languor, and a certain mischief in the eye, which were altogether involuntary. She scarcely knew, perhaps, the meaning of the word love, and yet not unwillingly ensnared those about her in the toils. But all this in her was innocent. She never thought of marrying.

Déruchette had the prettiest little hands in the world, and little feet to match them. Sweetness and goodness reigned throughout her person; her family and fortune were her uncle Mess Lethierry; her occupation was only to live her daily life; her accomplishments were the knowledge of a few songs; her intellectual gifts were summed up in her simple innocence; she had the graceful repose of the West Indian woman, mingled at times with giddiness and vivacity, with the teasing playfulness of a child, yet with a dash of melancholy. Her dress was somewhat rustic, and like that peculiar to her country-elegant, though not in accordance with the fashions of great cities; for she wore flowers in her bonnet all the year round. Add to all this an open brow, a neck supple and graceful, chestnut hair, a fair skin slightly freckled with exposure to the sun, a mouth somewhat large, but well-defined, and visited from time to time by a dangerous smile. This was Déruchette.’

‘Does not beauty confer a benefit upon us, even by the simple fact of being beautiful? Here and there we meet with one who possesses that fairy-like power of enchanting all about her; sometimes she is ignorant herself of this magical influence, which is, however, for that reason, only the more perfect. Her presence lights up the home; her approach is like a cheerful warmth; she passes by, and we are content; she stays awhile, and we are happy. To behold her is to live: she is the Aurora with a human face. She has no need to do more than simply to be: she makes an Eden of the house; Paradise breathes from her; and she communicates this delight to all, without taking any greater trouble than that of existing beside them. Is it not a thing divine to have a smile which, none know how, has the power to lighten the weight of that enormous chain which all the living, in common, drag behind them? Déruchette possessed this smile; we may even say that this smile was Déruchette herself. There is one thing which has more resemblance to ourselves than even our face, and that is our expression; but there is yet another thing which more resembles us than this, and that is our smile. Déruchette smiling was simply Déruchette.’

Toilers of the Sea, 1866

‘He had, moreover, purchased on credit, at the very entrance to the port of St. Sampson, a pretty stone-built house, entirely new, situate between the sea and a garden. On the corner of this house was inscribed the name of the “Bravees”. Its front formed a part of the wall of the port itself. and it was remarkable for a double row of windows: on the north, alongside a little enclosure filled with flowers, and on the south commanding a view of the ocean. It had thus two facades, one open to the tempest and the sea, the other looking into a garden filled with roses.’

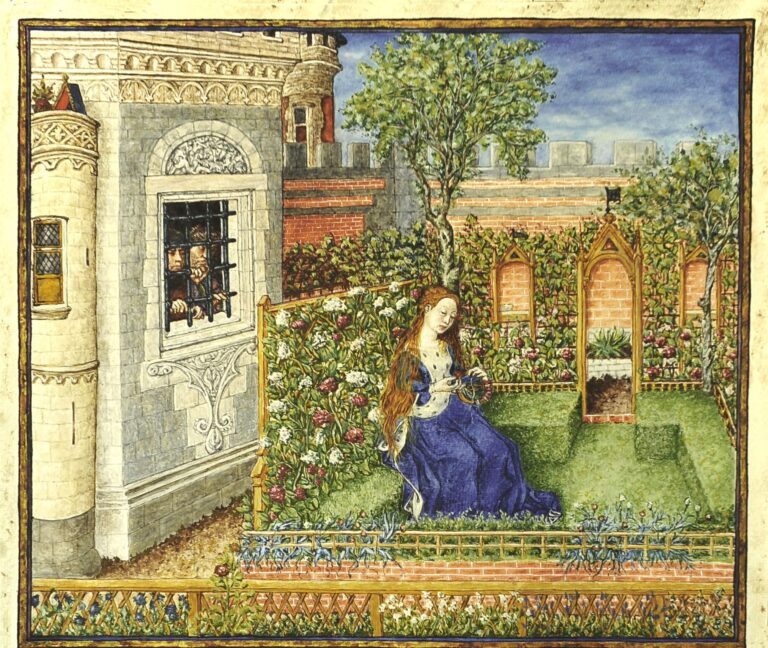

Déruchette’s garden is represented as a medieval hortus conclusus, an enclosed garden with a central female figure, taking its inspiration from illuminated manuscripts and the biblical Song of Solomon, its symbolism both religious and courtly. Such a garden had turf benches, fountains, trees, potted plants, walkways, enclosing walls, trellises, wattle fences and bowers; the female occupants would sit, walk, or play music, as strenous activities were not considered appropriate. Déruchette, in her safe space, was not allowed to ‘spoil her beautiful hands’; the ‘fountain sealed’ of the Song of Solomon, she could only water the plants; ‘a fountain of gardens, a well of living waters’. Innocent Gilliatt is tempted, but pure of heart, he is both a crusader knight on a vigil and a troubadour serenading his unobtainable beloved. He defeats a monster and completes his quest. His love, however, is forbidden; it is not to be of the earthly kind. Déruchette, an amalgam of the women in Victor Hugo’s life, represents the ‘ideal’ – both philosophical and feminine – that neither Gilliatt, nor Victor Hugo, nor indeed humanity can attain, thwarted as they are by human imperfection and the hand of fate.

Stuart Ewing wove a beautiful low willow fence to represent the garden, and Saumarez Park Walled Garden, Guernsey have very generously provided heritage varieties of vegetable for it. Victor Hugo has given Déruchette a very specific list of plants that she grew, and we have investigated their significance.

‘Lethierry allowed her to soil her fingers a little in gardening, and even in some kind of household duties: she watered her beds of pink hollyhocks, purple foxgloves, perennial phloxes, and scarlet herb bonnets. She took good advantage of the climate of Guernsey, so favourable to flowers. She had, like many other persons there, aloes in the open ground, and, what is more difficult, she succeeded in cultivating the Nepaulese cinquefoil. Her little kitchen-garden was scientifically arranged; she was able to produce from it several kinds of rare vegetables. She sowed Dutch cauliflower and Brussels cabbages, which she thinned out in July, turnips for August, endive for September, short parsnip for the autumn, and rampious for winter. Mess Lethierry did not interfere with her in this, so long as she did not handle the spade and rake too much, or meddle with the coarser kinds of garden labour. He had provided her with two servants, one named Grace, and the other Douce, which are favourite names in Guernsey. Grace and Douce, did the hard work of the house and garden, and they had the right to have red hands.’

Toilers of the Sea, 1866

‘Once seated there, he made no movement. He looked around; saw again the garden, the pathways, the beds of flowers, the house, the two windows of the chamber. The moonlight fell upon this dream. He felt it horrible to be compelled to breathe, and did what he could to prevent it.

He seemed to be gazing on a vision of paradise, and was afraid that all would vanish. It was almost impossible that all these things could be really before his eyes; and if they were, it could only be with that imminent danger of melting into air which belongs to things divine. A breath, and all must be dissipated! He trembled with the thought.

Before him, not far off, at the side of one of the alleys in the garden, was a wooden seat painted green. The reader will remember this seat.

Gilliatt looked up at the two windows. He thought of the slumber of some one possibly in that room. Behind that wall she was no doubt sleeping. He wished himself elsewhere, yet would sooner have died than go away. He thought of a gentle breathing moving a woman’s breast. It was she, that vision, that purity in the clouds, that form haunting him by day and night. She was there! He thought of her so far removed, and yet so near as to be almost within reach of his delight; he thought of that impossible ideal, drooping in slumber, and like himself, too, visited by visions; of that being so long desired, so distant, so impalpable, her closed eyelids, her face resting on her hand ; of the mystery of sleep in its relations with that pure spirit, of what dreams might come to one who was herself a dream. He dared not think beyond, and yet he did. He ventured on those familiarities which the fancy may indulge in, the notion of how much was feminine in that angelic being disturbed his thoughts. The darkness of night emboldens timid imaginations to take these furtive glances. He was vexed within himself, feeling on reflection as if it were profanity to think of her so boldly; yet still constrained, in spite of himself, he tremblingly gazed into the invisible. He shuddered almost with a sense of pain as he imagined her room, a petticoat on a chair, a mantle fallen on the carpet, a band unbuckled, a handkerchief. He imagined her corset with its lace hanging to the ground, her stockings, her boots.

His soul was among the stars.

The stars are made for the human heart of a poor man like Gilliatt not less than for that of the rich and great. There is a certain degree of passion by which every man becomes wrapped in a celestial light. With a rough and primitive nature this truth is even more applicable. An uncultivated mind is easily touched with dreams.

Delight is a fulness which overflows like any other. To see those windows was almost too much happiness for Gilliatt.

Suddenly he looked, and saw her.

From the branches of a clump of bushes, already thickened by the spring, there issued with a spectral slowness a celestial figure, a dress, a divine face, almost a shining light beneath the moon.

Gilliatt felt his powers failing him : it was Déruchette.’

The Toilers of the sea, 1866