Yucca 'Bright Star'

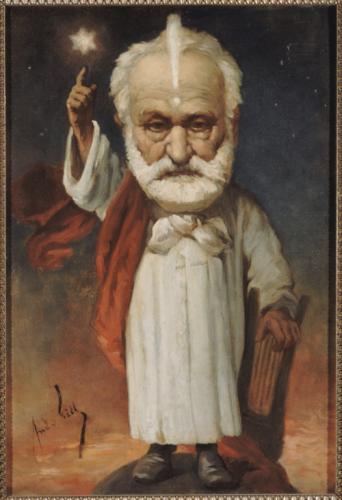

For Victor Hugo, stars represent the Ideal, amongst which the angels live; amongst these angels will be pure souls who have reached their rightful last resting place. They are a symbol of hope and are amongst the most important motifs in his work. A famous caricature represents him as a lamplighter, illuminating the stars.

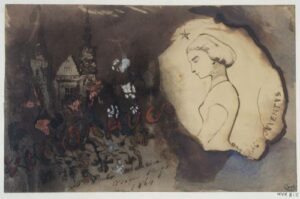

Here, in this celebrated drawing given as a New Year present to his friend Paul Meurice in 1863, Victor Hugo depicts a melancholy young woman with a star above her head. The drawing is called ‘Broken Youth’; it was assumed for a long time that it was a depiction of Victor Hugo’s eldest daughter Léopoldine, who drowned aged 19 in 1843. However, the figure resembles his younger daughter, Adèle, who had just a few months before fled from Guernsey in secret to search for her English lover. Both his daughters were now lost to him, and Adèle’s sad reclusivity in Guernsey, her poor choices, and her (for her parents) shocking and unexpected escape by ship to an unknown fate is reflected in his Guernsey novel, The Toilers of the Sea. In Hugo’s work, although kindly stars watch over the sailor and act as guide, they cannot protect him or her. Nevertheless, the star in the image shows that Hugo believes God is present and that there is always hope that she will return safely.

In a poem called ‘The function of the child‘, in La Légende des Siècles, Hugo writes of how a child’s intervention can sometimes cause a whole nation to reconsider a course of action, or to protest about an injustice: how, ‘Following the tide of an angry people/ Justice, terrifying Fury without her blindfold,/ Stands tall, with on her brow Pardon, that star!’

Victor Hugo’s short poem ‘Extase (Ecstasy),’ in translation; here God is present in and recognised as master by both the stars, representatives of the immaterial air and light, and the sea, so often for the poet the symbol of the material – the water and the earth. Even the dark depths of the sea, to be feared, are God’s work, part of the natural world, and for Hugo God is to be found within.

Victor Hugo sometimes conflates stars and flowers. In a poem about his childhood, he says he spent time observing ‘the stars in bloom and the shining flowers’. This is the same idea he expresses in the poem ‘Unity‘, where a daisy realises she can compare herself to the sun. Everything is God’s work, no matter how humble, and angels in various forms – we may never recognise them – may visit us to help us on our path towards the Ideal. Stars and flowers, symbols of God, may be found anywhere – on the brow of a child, for example.

In the frost, in the gale, a poor man was going past.

…

‘Come in and warm up,’ I bellowed, What is your name?’

He said, ‘I am the poor.’ I took his hand,

‘Come, Sir,’ I told him. I got him a bowl of milk.

He was shivering with cold, the old fellow; he talked, and

I answered without hearing, my thoughts elsewhere.

‘Your clothes are all wet, ‘I said; ‘You should hang them in front of

The fireplace.’ He moved closer to the fire.

His cloak, moth-eaten, and formerly blue,

Slung right across the warm blaze,

Riddled with thousands of holes by the light of the flames,

Shrouded the hearth, and looked like a black starry sky.

Then, while he dried those wretched tatters,

Dripping with rain and ditch water,

I thought how this man was utterly steeped in prayer;

Deaf to what we were saying, I

Gazed at the cloth, in which I could see constellations.

‘The Beggar (Le Mendiant)‘, from Les Contemplations, 1856, translation in The Essential Victor Hugo*

‘Shooting Stars’

See the scintillating shower!

In one sheet of splend’rous shine –

Incandescent coals that pour

From the incense-dish divine,

And around us dew-drops shaken,

Mirror each a twinkling ray

‘Twixt the flowers that awaken

In this glory great as day.

Mists and fogs all vanish fleetly;

And the birds begin to sing,

Whilst the rain is murm’ring sweetly

As if angels echoing.

And methinks to show she’s grateful

For this seed from heaven come

Earth is holding up a plateful

Of the birds and buds a-bloom!

‘Tas de feu tombants’, Les Chansons de Rues et des bois (1865). [The Literary life and poetical works of Victor Hugo, Hurst, New York, 1888]

Les deux amants, sous la nue,

Songent, charmants et vermeils…

L’immensité continue

Ses semailles de soleils.

À travers le ciel sonore,

Tandis que, du haut des nuits,

Pleuvent, poussière d’aurore,

Les astres épanouis,

Tant de feux tombants qui perce

Le zénith vaste et bruni,

Braise énorme que disperse

L’encensoir de l’infini ;

En bas, parmi la rosée,

Étalant l’arum, l’oeillet,

La pervenche, la pensée,

Le lys, lueur de juillet,

De brume à demi noyée,

Au centre de la forêt,

La prairie est déployée,

Et frissonne, et l’on dirait

Que la terre, sous les voiles

Des grands bois mouillés de pleurs,

Pour recevoir les étoiles

Tend son tablier de fleurs.

From ‘Les Etoiles filantes‘

‘Once seated there, he made no movement. He looked around; saw again the garden, the pathways, the beds of flowers, the house, the two windows of the chamber. The moonlight fell upon this dream. He felt it horrible to be compelled to breathe, and did what he could to prevent it.

He seemed to be gazing on a vision of paradise, and was afraid that all would vanish. It was almost impossible that all these things could be really before his eyes; and if they were, it could only be with that imminent danger of melting into air which belongs to things divine. A breath, and all must be dissipated! He trembled with the thought.

Before him, not far off, at the side of one of the alleys in the garden, was a wooden seat painted green. The reader will remember this seat.

Gilliatt looked up at the two windows. He thought of the slumber of some one possibly in that room. Behind that wall she was no doubt sleeping. He wished himself elsewhere, yet would sooner have died than go away. He thought of a gentle breathing moving a woman’s breast. It was she, that vision, that purity in the clouds, that form haunting him by day and night. She was there! He thought of her so far removed, and yet so near as to be almost within reach of his delight; he thought of that impossible ideal, drooping in slumber, and like himself, too, visited by visions; of that being so long desired, so distant, so impalpable, her closed eyelids, her face resting on her hand ; of the mystery of sleep in its relations with that pure spirit, of what dreams might come to one who was herself a dream. He dared not think beyond, and yet he did. He ventured on those familiarities which the fancy may indulge in, the notion of how much was feminine in that angelic being disturbed his thoughts. The darkness of night emboldens timid imaginations to take these furtive glances. He was vexed within himself, feeling on reflection as if it were profanity to think of her so boldly; yet still constrained, in spite of himself, he tremblingly gazed into the invisible. He shuddered almost with a sense of pain as he imagined her room, a petticoat on a chair, a mantle fallen on the carpet, a band unbuckled, a handkerchief. He imagined her corset with its lace hanging to the ground, her stockings, her boots.

His soul was among the stars.

The stars are made for the human heart of a poor man like Gilliatt not less than for that of the rich and great. There is a certain degree of passion by which every man becomes wrapped in a celestial | light. With a rough and primitive nature this truth is even more applicable. An uncultivated mind is easily touched with dreams.

Delight is a fullness which overflows like any other. To see those windows was almost too much happiness for Gilliatt.

Suddenly he looked, and saw her.

From the branches of a clump of bushes, already thickened by the spring, there issued with a spectral slowness a celestial figure, a dress, a divine face, almost a shining light beneath the moon.

Gilliatt felt his powers failing him : it was Déruchette.’

The Toilers of the sea, 1866

*Blackmore, The Essential Victor Hugo, OUP (see bibliography)