Nature! soul, shade, life! o veilèd face! …

Text written in clouds and in marble too!

Bible made of waves, of mountains and of trees,

Of darkling night and heavenly blue!

Toute la lyre, probably 1854-55

‘The blue sky, the spring, nature serene,

The book of the birds and the gypsies.’

Throughout his work Victor Hugo exhorts children and adults alike to learn from the book of nature. Although this concept is much older than Victor Hugo, his approach is unusual in that he melds the idea of unfettered, unspoiled nature with that of the garden, which is usually walled. He contrasts the artificiality of the formal garden and the gaudy flowers within it with the joyousness and innocence of wild flowers and trees; his gardens contain running and still water, fruit, wells, birds and insects, reptiles, and all kinds of weeds and wild flowers. Of course, there is an analogy in this with the stunted and constricted nature of monarchy and the happy insouciance of a liberated people, ‘children’ who, freed from parental and monarchical constraints, can grow and progress as they are destined to.

There is very little difference to be found in his description of the ideal garden and of a natural landscape; his garden-landscapes can be often be assigned to no obvious date or century. The classical scenes he describes are similar, different only in that they are populated by nymphs, shepherds and fauns and the flora is a little more Mediterranean. Progress to the Ideal is made step-by-step; the world and its people have been the same throughout history, each a unchanging part of God, moving up and down on the ladder between heaven and earth.

For Victor Hugo, nature was both Church and school. However, as a young writer Victor Hugo made little mention of gardens. The first long description of a garden, or at least what purports to be a very clear memory of an episode in his own life which took place in a garden, occurs in his first overtly ‘socialist’ work, the novella The Last Day of a Condemned Man, published in 1829. However, the death of his elder brother, Eugène, in 1837, shook him to the core, and he began to write of their childhood and particularly of their mother. Hugo’s interest in botany may have been encouraged by his mother and his boyhood tutor, and especially by his friend and early travel companion, poet and writer Charles Nodier, ten years his senior, who was an avid botanist and book-collector.

This poem of God’s which is worth more than mine,

Wherein the child may pluck the flower, living stanza …’

‘A des oiseaux envolés’, Les voix intérieures, poem dated 1837

Hugo’s mother, Sophie, was extremely fond of flowers, which she took great enjoyment in cultivating at their garden of Les Feuillantines in Paris. Hugo wrote several poems and essays about this garden, and refers to it many times, often with the shadow of death attached. His parents did not get on; his father General Léopold-Sigisbert Hugo was in Spain and his mother alone had responsibility for the Hugo children. It was an enclosed garden, the site of an old convent, with a ruined chapel at the bottom of the garden, covered with shells – Hugo was perhaps moved when he saw walls in Guernsey similarly covered in ormer shells. Mme Hugo hid her lover General Lahorie, Hugo’s godfather, who had fallen foul of Napoleon, in the old sacristy of the Chapel. He remained there living like a hermit for a year. Hugo’s idyll here with his surrogate father was destroyed when the police broke into the garden and arrested Lahorie, who after conspiring again was eventually executed. The garden’s protective bubble, and that of his mother, had been breached.

‘The little flowers of gold, the little flowers of blue,

Waving their bouquets to greet him, affect

Small studied airs, or airs openly flirtatious,

And, because it suits a belle to be not shy,

They say, ‘Ooh! That’s our lover walking by!’

‘The poet goes off into the fields‘, Les Contemplations, 1856

The enclosed garden at the Feuillantines is echoed in the garden of Déruchette in Toilers of the Sea. With the strong presence of a female beloved yet untouchable, and with a hint of almost religious mystery, they both have elements of the hortus conclusus, the medieval motif of a walled garden in which the Virgin Mary tends her plants, often medicinal. This is particularly evident in the description of Déruchette’s garden at Les Bravées, which clearly evokes an illuminated manuscript. As such it can be associated with his late daughter Léopoldine, who as a teenager was depicted in a portrait examining a medieval missal, who wears a poppy in her hair – as will the fictional Cosette years later – and who is represented by Hugo in his poetry as a lily. Les Bravées is a mystical garden brought down to earth by elements of humour and evocation of everyday life. Nevertheless, Déruchette behind her walls remains very much the immaculate object of troubadour Gilliatt’s courtly love and serenades. Her meeting with Ebenezer in the garden, where with his golden halo of hair he mesmerises her with his words, evokes depictions of the Annunciation.

Gardens play a large part in Les Misérables. The Jardin du Luxembourg, the public park built in the early 17th century as a royal garden, was now a suitably republican but still formal setting for the long-drawn out courtship of Marius and Cosette, who pass before each other like 17th-century dancers at a courtly ball, and fall for each other without exchanging a word, in an echo of Romeo and Juliet. Victor Hugo later laments how Haussmann’s remodelling of part of the old Jardin de Luxembourg destroyed Les Feuillantines, which was next door; a bomb in the Franco-Prussian War finished it off. It remained alive in his memory, however; all the more poignant as the remodelling of Paris took place at the order of his enemy, Napoleon III. Jean Valjean, having lived like General Lahorie as a wanted fugitive in a convent garden full of children’s happy voices, takes grown-up Cosette to live in a ‘pavilion’ in the rue Plumet, a nod again to the medieval; Victor Hugo’s father, who gave his blessing to Hugo’s marriage, lived in the actual rue Plumet and died there. Cosette and Valjean’s house is guarded from the road by an iron gate and a wild garden within, with a secret path from a walled paradise to the ‘Babylon’ of Paris. Valjean, the watchman, again inhabits an outhouse at the bottom of the garden. But even he cannot prevent Marius from breaking into his idyll; his mother’s magic garden, full of mystery, is exchanged for a place full of rampant nature and fertility, just right for the heady but secret courtship of Cosette and Marius. Victor Hugo acknowledges here his rejection of his mother’s monarchism and his acceptance of the politics of his father; he recognises that his father gave his blessing to the marriage that his mother had forbidden. In the book as in life, Marius is about to take Valjean’s place as the head of the family.

In Toilers of the sea, Gilliatt has a garden at the very edge of the sea, in which he grows what he needs. What he knows of plant lore and gardening he has learnt from his late mother, who has left him her old books – one on growing rhubarb – which the ignorant Guernsey folk assume are books of black magic. Here we may see echoes of The Tempest; Gilliatt, a pure and innocent but foreign soul, is mistrusted by the locals as a Caliban and his mother as a Sycorax, with a touch of Prospero in his ivory tower. Thus did the Guernsey people distrust Victor Hugo, the Frenchman, and his motives. We see Gilliatt as a he really is, living a monastic life in his hermit’s lodge, freeing the birds like St Francis, a fisherman as the apostles were – a life into which Déruchette makes an unexpected interruption. When he learns Miss Déruchette likes seakale, his innocent reaction – perhaps too, he is secretly curious about her feminine tastes – is to grow some himself. This maritime vegetable, easy to cultivate on the rocky shore where Giliatt has his garden, and which tastes very like asparagus, was grown by Hugo at Hauteville House; he was fond of actual asparagus, which he also grew, as well as early potatoes and gooseberries. Juliette Drouet, Hugo’s mistress, had a kitchen garden in her house at Hauteville with cherry and pear trees, and like Déruchette she kept chickens and other fowl.

Hugo’s house in Jersey, Marine Terrace, had a long conservatory in which the Hugo family spent much time and where many of the famous photographs of that period were taken. Hugo’s garden at Marine Terrace, however, was virtually bare. He was happy, he said, with a few marigolds; let nature have her way; as his daughter Adèle recorded in her journal, he withstood the exhortations of his family and friends to make more of it. When Englishwoman Gertrude Tennant holidayed in Guernsey in 1862, she was a frequent visitor to Hauteville House. On her first visit to the by then celebrated residence she was accompanied by Hugo’s old friend, Hennett de Kesler. She noted with dismay that the garden had hardly anything in it. Kesler read her the description of the garden at the rue Plumet twice, in a significant tone of voice. In fact, the garden had flowers, enough for Juliette Drouet to remark that she saw departing visitors cut bouquets to take home with them. The garden is described by Hugo’s son Charles as full of plants, flowering shrubs and trees in 1861; it was partially remodelled in 1864 following a storm. Hugo’s conservatory, and of course his famous glass lookout, allowed him to be close to nature while still indoors. He grew luscious grapes he was very proud of and would give as gifts. The Guernsey photographer Arsène Garnier wrote of the many types of flower Hugo cultivated – the scent of geraniums, heliotrope, mignonette and so on from his conservatory are said to have perfumed the house. That commentators would remark on his liking for perfumed flowers is not surprising; their scent not only reminded him of times past, but was also symbolic: flowers have their roots in the material, the earth, but let their perfume out to the air and light, the immaterial world of the Ideal to which all Nature, including humanity, aspires. The house itself is decorated throughout with motifs and designs taken from nature, while the garden, as if it were an extension of the inside space, features inscriptions engraved on stone, as can be found in the house.

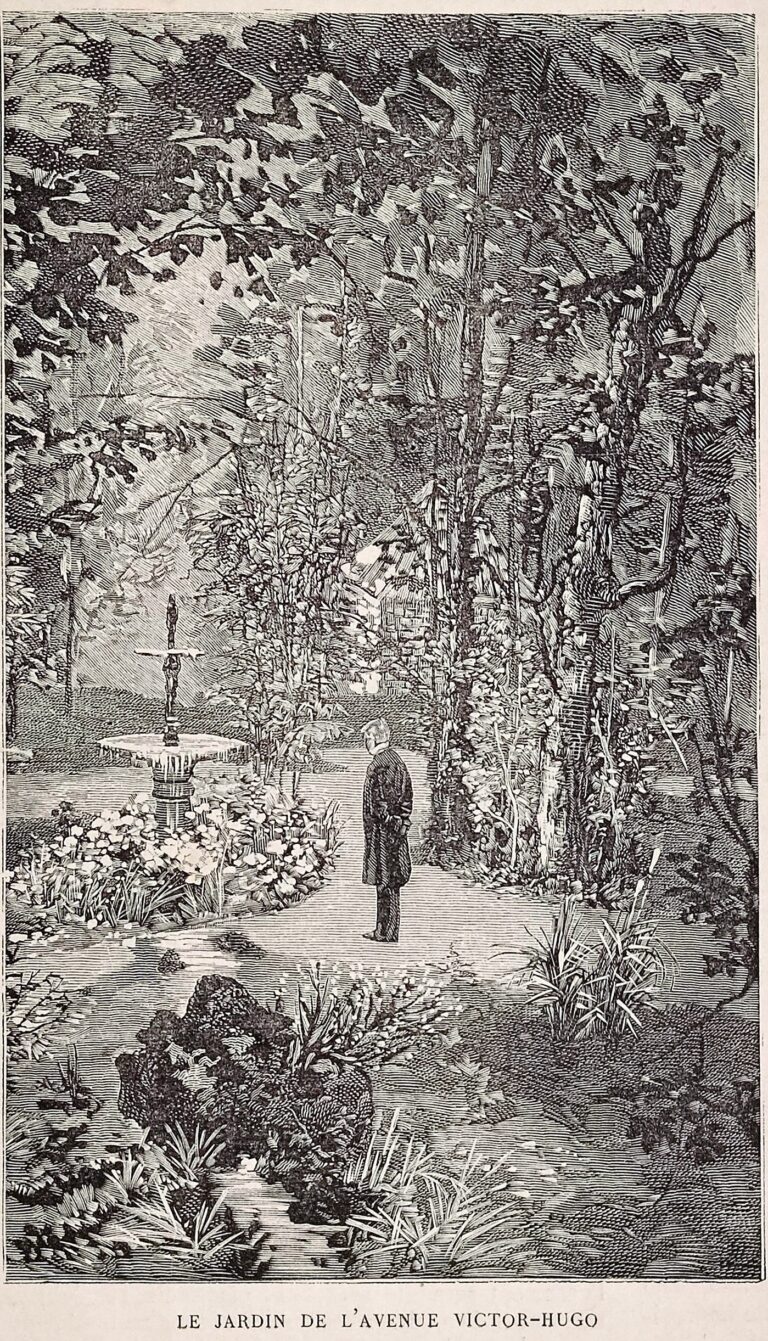

Hugo brought with him from his previous house in Paris a fountain in terracotta which he placed in the middle of Hauteville House garden. It served as a place for taking portraits and was the subject of one of his poems. This pre-Revolution rococo fountain and pond echo the garden at the Feuillantines, which had a well in which he and his brothers had fun pretending there was a monster. The fountain takes its proper place as an important element in Hugo’s mystic garden; but it is interesting to note that this monarchical fountain was known as ‘The Fountain of Serpents’. Evil was always present, even in this Garden of Eden.

Hugo’s novel of 1869, The Man who laughs, written in Guernsey, is set in the world of the travelling theatre, but even here past trauma forces its way in: the hero, Gwynplaine, like General Lahorie, is roughly arrested while inside his home, a showman’s caravan, known as the Green-Box – a version of the garden-house that was Hauteville House.

Je me penche attendri sur les bois et les eaux,

Rêveur, grand-père aussi des fleurs et des oiseaux ;

J’ai la pitié sacrée et profonde des choses ;

J’empêche les enfants de maltraiter les roses ;

Je dis : N’effarez point la plante et l’animal ;

Riez sans faire peur, jouez sans faire mal.

Jeanne et Georges, fronts purs, prunelles éblouies,

Rayonnent au milieu des fleurs épanouies ;

J’erre, sans le troubler, dans tout ce paradis ;

Je les entends chanter, je songe, et je me dis

Qu’ils sont inattentifs, dans leurs charmants tapages,

Au bruit sombre que font en se tournant les pages

Du mystérieux livre où le sort est écrit,

Et qu’ils sont loin du prêtre et près de Jésus-Christ.

‘Aux champs’, Toute la lyre (1888-93)

Victor Hugo had a pleasant garden with a pond and weeping willows at his last house on the Avenue d’Eylau in Paris, later Avenue Victor Hugo, but it is at Hauteville House that Hugo brings, one might say, the outside in and the inside out; the house and garden together stand as an entwined work of art and philosophy, a monumental poem that Hugo himself recognised ‘had something of himself in it’.

Claude Gély, Victor Hugo, poète de l’intimité &c … 1969; Florence Naugrette, ed., Gertrude Tennant, Mes Souvenirs sur Hugo et Flaubert, &c, 2020; Gérard Audinet, Le Jardin de Victor Hugo &c … 2020